Important Places

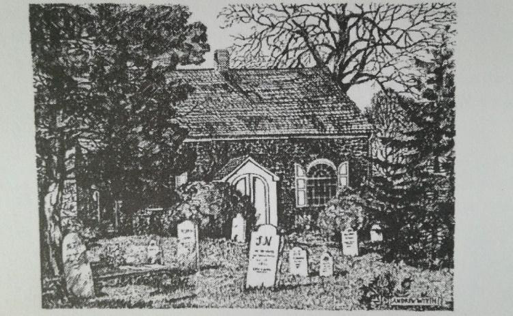

“Beggarstown School in Northwestern Philadelphia,” On NRHP, Wikimedia Commons

“Beggarstown School in Northwestern Philadelphia,” On NRHP, Wikimedia Commons

Beggarstown School

The Beggarstown School was built on the Germantown Road around 1740. This colonial style schoolhouse is one of the few buildings around today that was standing during the various British marches up and down this early highway. For almost three hundred years it has preserved its style and original flavor, despite having a couple of slight alterations. A place where children once learned to read, write and do arithmetic, the school is owned by the St. Michael's Evangelical Lutheran Church. During the Battle of Whitemarsh the British troops wreaked havoc along Germantown Road, all throughout Chestnut Hill, Beggarstown, and Cresheim Village. They set fire to buildings and stole from the townspeople. The Beggarstown school survived these burnings and still stands today.

The Beggarstown School was built on the Germantown Road around 1740. This colonial style schoolhouse is one of the few buildings around today that was standing during the various British marches up and down this early highway. For almost three hundred years it has preserved its style and original flavor, despite having a couple of slight alterations. A place where children once learned to read, write and do arithmetic, the school is owned by the St. Michael's Evangelical Lutheran Church. During the Battle of Whitemarsh the British troops wreaked havoc along Germantown Road, all throughout Chestnut Hill, Beggarstown, and Cresheim Village. They set fire to buildings and stole from the townspeople. The Beggarstown school survived these burnings and still stands today.

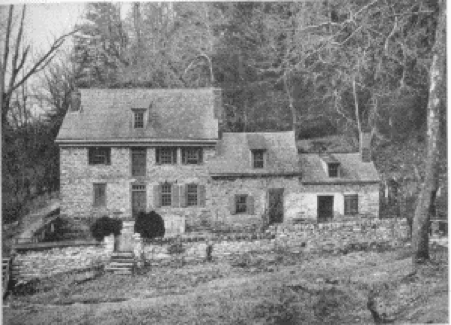

“Glen Fern” along the Wissahickon Creek below Chestnut Hill - located along Livezey Lane in Philadelphia, Frank Cousins and Phil M. Riley, “The Colonial Architecture of Philadelphia,” Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1920, Web.

“Glen Fern” along the Wissahickon Creek below Chestnut Hill - located along Livezey Lane in Philadelphia, Frank Cousins and Phil M. Riley, “The Colonial Architecture of Philadelphia,” Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1920, Web.

Chestnut Hill

Bordering on the Wissahickon Creek at its base, Chestnut Hill is the area directly north west of Beggarstown and Cresheim Village on Germantown Avenue. Similarly, to those two areas, Chestnut Hill was predominantly German during the colonial years of America. To add to the German heritage, parts of Chestnut Hill and Germantown were made up of Hollanders and Swiss Mennonites previously settled in Holland, as well as French Huguenots who had fled the cancellation of the Edict of Nantes. During the Battle of Whitemarsh, Chestnut Hill fell into Howe’s hands on December 5th and 6th. Howe himself took up headquarters in the house of Mathias Bush, an important Jewish businessman, landowner and supporter of the revolution. The Bush house once stood at the intersection of Germantown Avenue and Bethlehem Pike. The rest of the British troops were positioned around Chestnut Hill until they departed late on the 6th. While many buildings were destroyed when the British burned the streets that night, Chestnut Hill has kept up a unique old fashioned taste evident in the cobblestones on Germantown Avenue and the colonial style homes.

Bordering on the Wissahickon Creek at its base, Chestnut Hill is the area directly north west of Beggarstown and Cresheim Village on Germantown Avenue. Similarly, to those two areas, Chestnut Hill was predominantly German during the colonial years of America. To add to the German heritage, parts of Chestnut Hill and Germantown were made up of Hollanders and Swiss Mennonites previously settled in Holland, as well as French Huguenots who had fled the cancellation of the Edict of Nantes. During the Battle of Whitemarsh, Chestnut Hill fell into Howe’s hands on December 5th and 6th. Howe himself took up headquarters in the house of Mathias Bush, an important Jewish businessman, landowner and supporter of the revolution. The Bush house once stood at the intersection of Germantown Avenue and Bethlehem Pike. The rest of the British troops were positioned around Chestnut Hill until they departed late on the 6th. While many buildings were destroyed when the British burned the streets that night, Chestnut Hill has kept up a unique old fashioned taste evident in the cobblestones on Germantown Avenue and the colonial style homes.

Clifton House (Sandy Run Tavern)

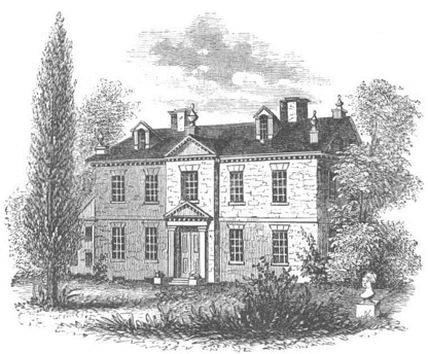

The Clifton house is presently the home of the Fort Washington Historical Society. Yet during the days of the Whitemarsh encampment a building at this location housed Washington’s Quartermaster General, Stephen Moylan, as well as his companion Colonel Clement Biddle. Weary soldiers would cram themselves into the space, eager to warm their bodies from the deathly cold air outside. In the times surrounding the Revolutionary War, the Clifton House was a tavern called the Sandy Run Inn, as the Sandy Run Creek ran near to it. Unfortunately, the original building was destroyed. Rebuilt in 1801, the place still proved a convenient stop for travelers to stay the night. Again in 1857, Clifton House suffered ruin by a devastating fire, only to be rebuilt, this time adhering to the architectural style of the mid nineteenth century. After being taken over by Pennsylvania in 1928, the Historical Society of Fort Washington rescued the Clifton House from its hard times. Today the house is open to visitors to consider the deep histories and stories that were once part of its halls and the general area.

The Clifton house is presently the home of the Fort Washington Historical Society. Yet during the days of the Whitemarsh encampment a building at this location housed Washington’s Quartermaster General, Stephen Moylan, as well as his companion Colonel Clement Biddle. Weary soldiers would cram themselves into the space, eager to warm their bodies from the deathly cold air outside. In the times surrounding the Revolutionary War, the Clifton House was a tavern called the Sandy Run Inn, as the Sandy Run Creek ran near to it. Unfortunately, the original building was destroyed. Rebuilt in 1801, the place still proved a convenient stop for travelers to stay the night. Again in 1857, Clifton House suffered ruin by a devastating fire, only to be rebuilt, this time adhering to the architectural style of the mid nineteenth century. After being taken over by Pennsylvania in 1928, the Historical Society of Fort Washington rescued the Clifton House from its hard times. Today the house is open to visitors to consider the deep histories and stories that were once part of its halls and the general area.

Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Vol. II, Chapter IV. New York: Harper and Brother, Publishers, Franklin Square, 1859, Web.

Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Vol. II, Chapter IV. New York: Harper and Brother, Publishers, Franklin Square, 1859, Web.

Cliveden House

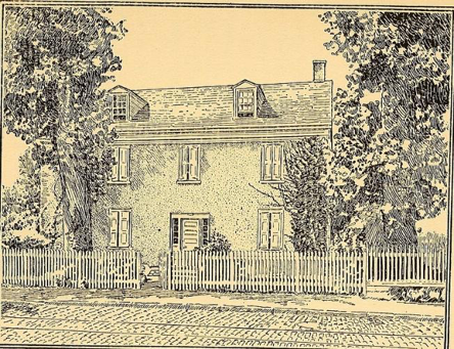

The Cliveden House, otherwise known as the Chew Mansion, was built by the attorney general of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Chew in the 1760s. The house, located on Germantown Avenue, was meant to be his country estate. However, due to his questionable support for the patriots at the onset of the revolution, Chew’s political position was taken away and he was even imprisoned for a brief time. In October of 1777, it was British soldiers that occupied the Chew mansion. On the 4th of October, the Battle of Germantown struck and Cliveden became the epicenter. (The Americans were trying to recapture Philadelphia, but the British would prove to be too strong in their defense.) About 100 British soldiers under the command of Lt. Colonel Thomas Musgrave retreated into the mansion after their position was overrun by Continental forces. Here Musgrave and his men put up a valiant resistance against earnest assaults to dislodge them. At one point in the fighting the Americans even used artillery to fire upon the house which did almost nothing to help their cause, since the walls were so thick. Musgrave and his men held forth until the Continentals were forced to retreat. The house was left heavily damaged. Two months later the British marched along Germantown Avenue again past the wreckage of the Chew mansion on their way to fight Washington at Whitemarsh. A year after this Benjamin Chew was permitted to return to his house and begin its repair. The mansion remained almost completely in the ownership of the Chews until 1972 when the house was transferred to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The Cliveden House, otherwise known as the Chew Mansion, was built by the attorney general of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Chew in the 1760s. The house, located on Germantown Avenue, was meant to be his country estate. However, due to his questionable support for the patriots at the onset of the revolution, Chew’s political position was taken away and he was even imprisoned for a brief time. In October of 1777, it was British soldiers that occupied the Chew mansion. On the 4th of October, the Battle of Germantown struck and Cliveden became the epicenter. (The Americans were trying to recapture Philadelphia, but the British would prove to be too strong in their defense.) About 100 British soldiers under the command of Lt. Colonel Thomas Musgrave retreated into the mansion after their position was overrun by Continental forces. Here Musgrave and his men put up a valiant resistance against earnest assaults to dislodge them. At one point in the fighting the Americans even used artillery to fire upon the house which did almost nothing to help their cause, since the walls were so thick. Musgrave and his men held forth until the Continentals were forced to retreat. The house was left heavily damaged. Two months later the British marched along Germantown Avenue again past the wreckage of the Chew mansion on their way to fight Washington at Whitemarsh. A year after this Benjamin Chew was permitted to return to his house and begin its repair. The mansion remained almost completely in the ownership of the Chews until 1972 when the house was transferred to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Charles Francis Jenkins, 1865-1951 Site and Relic Society of Germantown (Philadelphia, Pa.),

The Guidebook to Historic Germantown, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Francis Jenkins, 1865-1951 Site and Relic Society of Germantown (Philadelphia, Pa.),

The Guidebook to Historic Germantown, Wikimedia Commons

Cresheim Village and Beggarstown

The area that is presently known as Mount Airy was once part of the larger Germantown Village. The original Germantown was founded 1683 and given importance by Francis Daniel Pastorius, a Lutheran Pietist and one of several who first protested slavery in America. The area was home to quite a lot of Germans, hence the name. Both Dunker and Lutheran churches were prominent in the area. Beggarstown, or Bettelhausen, was comprised of the “sidelands” of Germantown proper. The community owes its name to the first person to build a house in the sidelands - John Pettikoffer, a beggar. Contrary to its name, the people of Beggarstown were said to be economically stable during and after the Revolutionary War. When it came time for the Philadelphia Campaign, Cresheim Village and Beggarstown were frequent stops on the map for the British. In the early days of their occupation of Philadelphia, Howe stationed troops here and around Germantown to scout out for Washington’s men. In October, the Battle of Germantown took place amongst these streets and houses. Then, in December, the British marched once again through Beggarstown and Cresheim Village on their way to Whitemarsh. The communities suffered extensive depredations by the British and Hessians during their retreat from Chestnut Hill on the night of December 6 and 7, 1777. In the nineteenth century, the word “Franklinville” circled around the town as an alternate name for the village. However, the name “Beggarstown” survived until the community was eclipsed by the ever-expanding City of Philadelphia. What was Beggarstown existed roughly between Upsal Street and Gorgas Lane along the Germantown Road. The Village of Cresheim was further up toward Chestnut Hill toward Cresheim Creek. An old edifice at the corner of Germantown and Gowen is purported to be of pre-Revolutionary vintage. Cresheim Village takes its name from the area of Germany from which the first settlers emigrated.

The area that is presently known as Mount Airy was once part of the larger Germantown Village. The original Germantown was founded 1683 and given importance by Francis Daniel Pastorius, a Lutheran Pietist and one of several who first protested slavery in America. The area was home to quite a lot of Germans, hence the name. Both Dunker and Lutheran churches were prominent in the area. Beggarstown, or Bettelhausen, was comprised of the “sidelands” of Germantown proper. The community owes its name to the first person to build a house in the sidelands - John Pettikoffer, a beggar. Contrary to its name, the people of Beggarstown were said to be economically stable during and after the Revolutionary War. When it came time for the Philadelphia Campaign, Cresheim Village and Beggarstown were frequent stops on the map for the British. In the early days of their occupation of Philadelphia, Howe stationed troops here and around Germantown to scout out for Washington’s men. In October, the Battle of Germantown took place amongst these streets and houses. Then, in December, the British marched once again through Beggarstown and Cresheim Village on their way to Whitemarsh. The communities suffered extensive depredations by the British and Hessians during their retreat from Chestnut Hill on the night of December 6 and 7, 1777. In the nineteenth century, the word “Franklinville” circled around the town as an alternate name for the village. However, the name “Beggarstown” survived until the community was eclipsed by the ever-expanding City of Philadelphia. What was Beggarstown existed roughly between Upsal Street and Gorgas Lane along the Germantown Road. The Village of Cresheim was further up toward Chestnut Hill toward Cresheim Creek. An old edifice at the corner of Germantown and Gowen is purported to be of pre-Revolutionary vintage. Cresheim Village takes its name from the area of Germany from which the first settlers emigrated.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Dawesfield [Whitpain Township, Montgomery County], 1855, Watercolor on paper, 11 x 15 in., (The Schwarz Gallery, Philadelphia Collection XLVII, Nov. 1991)

Edmund Darch Lewis, Dawesfield [Whitpain Township, Montgomery County], 1855, Watercolor on paper, 11 x 15 in., (The Schwarz Gallery, Philadelphia Collection XLVII, Nov. 1991)

Dawsefield

In 1728, Abraham Dawes built a 300-acre colonial estate that would one day become Washington’s headquarters. Dawesfield lies along Lewis Lane in Whitpain Township, close to present day Ambler, and it was here that the Continental troops camped from October 21 through November 2, 1777 just prior to their move to Whitemarsh. After the Battle of Germantown on October 4th, the Americans had been journeying throughout Montgomery Township, looking for a place to camp. It wasn’t until they found Whitpain that they settled for a time. A number of events occurred at Dawesfield during the Whitpain encampment, including the court-martial of General “Mad Anthony” Wayne dealing with the “Paoli Massacre.” He was exonerated. A council of war was also held at this location to determine the army’s next course of action. During this encampment, Dawesfield was owned by a man named James Morris. Not only did Washington sleep here, but so did Lafayette. The house can still be clearly seen from Lewis Lane.

In 1728, Abraham Dawes built a 300-acre colonial estate that would one day become Washington’s headquarters. Dawesfield lies along Lewis Lane in Whitpain Township, close to present day Ambler, and it was here that the Continental troops camped from October 21 through November 2, 1777 just prior to their move to Whitemarsh. After the Battle of Germantown on October 4th, the Americans had been journeying throughout Montgomery Township, looking for a place to camp. It wasn’t until they found Whitpain that they settled for a time. A number of events occurred at Dawesfield during the Whitpain encampment, including the court-martial of General “Mad Anthony” Wayne dealing with the “Paoli Massacre.” He was exonerated. A council of war was also held at this location to determine the army’s next course of action. During this encampment, Dawesfield was owned by a man named James Morris. Not only did Washington sleep here, but so did Lafayette. The house can still be clearly seen from Lewis Lane.

Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Vol. II, Chapter IV. New York:

Harper and Brother, Publishers, Franklin Square, 1859, Web.

Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Vol. II, Chapter IV. New York:

Harper and Brother, Publishers, Franklin Square, 1859, Web.

Emlen House

During the encampment at Whitemarsh, the Emlen House played an important role as the location of Washington’s headquarters. It was here that Washington intercepted the infamous “Conway Cabal,” and the location served as the origin of over a hundred dispatches by the general during the time including correspondence with General Howe regarding possible prisoner exchanges. Directly following the Battle of Edge Hill on December 7 various soldiers were treated for wounds in the house before being sent to other locations. Before Washington ever set foot in its rooms, the building was constructed before 1745, more than thirty years prior to the onset of the Philadelphia campaign. The Emlen House was the summer estate of the wealthy Philadelphia merchant, George Emlen who died the year previous to the encampment in 1776, and is located just north of Pennsylvania Avenue near the encampments on Camp Hill. The house has been privately owned for many years by the Piszek family and has kept its original touch despite undergoing various renovations and surrounding development.

During the encampment at Whitemarsh, the Emlen House played an important role as the location of Washington’s headquarters. It was here that Washington intercepted the infamous “Conway Cabal,” and the location served as the origin of over a hundred dispatches by the general during the time including correspondence with General Howe regarding possible prisoner exchanges. Directly following the Battle of Edge Hill on December 7 various soldiers were treated for wounds in the house before being sent to other locations. Before Washington ever set foot in its rooms, the building was constructed before 1745, more than thirty years prior to the onset of the Philadelphia campaign. The Emlen House was the summer estate of the wealthy Philadelphia merchant, George Emlen who died the year previous to the encampment in 1776, and is located just north of Pennsylvania Avenue near the encampments on Camp Hill. The house has been privately owned for many years by the Piszek family and has kept its original touch despite undergoing various renovations and surrounding development.

Frank Cousins and Phil M. Riley, “The Colonial Architecture of Philadelphia,” Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1920, Web.

Frank Cousins and Phil M. Riley, “The Colonial Architecture of Philadelphia,” Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1920, Web.

Hope Lodge

Hope Lodge is unique amongst many of the homes in Whitemarsh. Built around 1740, it has been perfectly preserved and kept up for nearly 300 years. In 1777 Hope Lodge was owned by a man named William West who supported the resistance of British taxes. West graciously allowed Washington’s chief surgeon, John Cochran, and other physicians to stay at his house when they arrived in November. Whether the house was used as a full-scale hospital at the time has been debated, but either way the house was opened to help the sick and injured soldiers during the early onslaught of brutal winter weather. After West’s death, the house was purchased by Henry Hope, hence the name Hope Lodge. After a series of ownerships Hope Lodge was transferred over to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1957, and it remains as a museum and relic of colonial and revolutionary America.

Hope Lodge is unique amongst many of the homes in Whitemarsh. Built around 1740, it has been perfectly preserved and kept up for nearly 300 years. In 1777 Hope Lodge was owned by a man named William West who supported the resistance of British taxes. West graciously allowed Washington’s chief surgeon, John Cochran, and other physicians to stay at his house when they arrived in November. Whether the house was used as a full-scale hospital at the time has been debated, but either way the house was opened to help the sick and injured soldiers during the early onslaught of brutal winter weather. After West’s death, the house was purchased by Henry Hope, hence the name Hope Lodge. After a series of ownerships Hope Lodge was transferred over to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1957, and it remains as a museum and relic of colonial and revolutionary America.

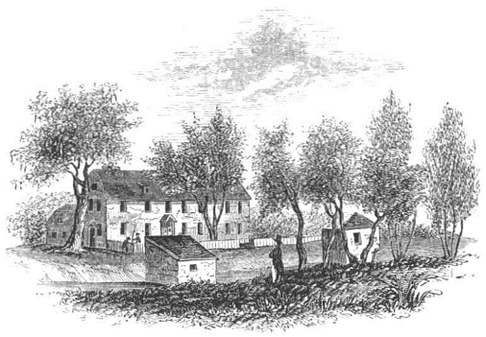

Xanthus Russell Smith (1839-1929). Farmstead at Shoemakertown [Montgomery County], 1876

Pencil on paper, 8 x 12 in., (The Schwarz Gallery, Philadelphia Collection LXIV, Jan. 1999)

Xanthus Russell Smith (1839-1929). Farmstead at Shoemakertown [Montgomery County], 1876

Pencil on paper, 8 x 12 in., (The Schwarz Gallery, Philadelphia Collection LXIV, Jan. 1999)

Shoemaker Mill

In 1746, Dorothy Penrose Shoemaker, one of the descendants of the first inhabitants of the area, began and operated a corn-grist mill along with Richard Mather and John Tyson. The mill was located at the intersection of Church Road and York Road along the Tookany Creek, and was standing during the Battle of Edgehill. On December 8th, 1777, the British began their retreat from Whitemarsh as Howe gradually withdrew his troops from their positions. Once the army was pulled together they made a stop at Shoemaker’s Mill where a group of Hessians destroyed and plundered the mill of its livestock and goods. In 1847, the place was repaired and purchased by Charles Bolster, whose family ran the mill until 1923. Unfortunately, Shoemaker’s mill was destroyed for good in 1927. The Richard Wall house, which stands at the location, is one of the oldest homes still existence in the region. It was built by the one bearings its name in 1683. Wall was an early Quaker in the area and in 1688 the second reading of Pastorius’ proclamation against slavery was read in the house.

In 1746, Dorothy Penrose Shoemaker, one of the descendants of the first inhabitants of the area, began and operated a corn-grist mill along with Richard Mather and John Tyson. The mill was located at the intersection of Church Road and York Road along the Tookany Creek, and was standing during the Battle of Edgehill. On December 8th, 1777, the British began their retreat from Whitemarsh as Howe gradually withdrew his troops from their positions. Once the army was pulled together they made a stop at Shoemaker’s Mill where a group of Hessians destroyed and plundered the mill of its livestock and goods. In 1847, the place was repaired and purchased by Charles Bolster, whose family ran the mill until 1923. Unfortunately, Shoemaker’s mill was destroyed for good in 1927. The Richard Wall house, which stands at the location, is one of the oldest homes still existence in the region. It was built by the one bearings its name in 1683. Wall was an early Quaker in the area and in 1688 the second reading of Pastorius’ proclamation against slavery was read in the house.

“The Little Church at White Marsh,”

With permission by St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, Whitemarsh, PA

“The Little Church at White Marsh,”

With permission by St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church, Whitemarsh, PA

St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church

St. Thomas Episcopal Church first existed as a log edifice. It was built in 1698 by Edward Farmar, one of the early settlers in the area. This structure was burned and then replaced by a stone church in 1710. It then became known as the “The Little Church at White Marsh” for about 100 years. In 1740 George Whitefield, the famous English evangelist, preached here to about 2,000 people. Church Road, so-called because it served as a conduit between this location and Trinity Church Oxford in present day Northeast Philadelphia, in colonial days ran right up and over the hill in front of the church building. For a time, the two churches shared a pastor. Not only did the location serve as an advance post for Washington’s troops during the Whitemarsh encampment, it also saw action weeks earlier on October 4. Following the American loss and retreat at the Battle of Germantown the British trailed in pursuit of the Americans who were headed in the direction of Skippack Pike. The British, under the command of William Howe, took control of the church and hill and fired cannon balls down onto the fleeing continentals. For another two months “The Little Church at White Marsh” witnessed the numerous events and trials that plagued the Americans during their encampment at Whitemarsh. During the war the church was largely abandoned and no records of the time are extant. In 1818 another church building was erected followed by the present structure in the 1850s. The blue poles in the graveyard across from the main entrance mark the original outlay of the early church.

St. Thomas Episcopal Church first existed as a log edifice. It was built in 1698 by Edward Farmar, one of the early settlers in the area. This structure was burned and then replaced by a stone church in 1710. It then became known as the “The Little Church at White Marsh” for about 100 years. In 1740 George Whitefield, the famous English evangelist, preached here to about 2,000 people. Church Road, so-called because it served as a conduit between this location and Trinity Church Oxford in present day Northeast Philadelphia, in colonial days ran right up and over the hill in front of the church building. For a time, the two churches shared a pastor. Not only did the location serve as an advance post for Washington’s troops during the Whitemarsh encampment, it also saw action weeks earlier on October 4. Following the American loss and retreat at the Battle of Germantown the British trailed in pursuit of the Americans who were headed in the direction of Skippack Pike. The British, under the command of William Howe, took control of the church and hill and fired cannon balls down onto the fleeing continentals. For another two months “The Little Church at White Marsh” witnessed the numerous events and trials that plagued the Americans during their encampment at Whitemarsh. During the war the church was largely abandoned and no records of the time are extant. In 1818 another church building was erected followed by the present structure in the 1850s. The blue poles in the graveyard across from the main entrance mark the original outlay of the early church.

Sabra Smith, “Thomas Fitzwater House”, My Time Machine - Buildings, Places, People and Things, 24 June, 2009, Web, 14 July, 2017

Sabra Smith, “Thomas Fitzwater House”, My Time Machine - Buildings, Places, People and Things, 24 June, 2009, Web, 14 July, 2017

Thomas Fitzwater House

The Thomas Fitzwater House, located on Limekiln Pike in Upper Dublin, was one of the first houses built in Pennsylvania after William Penn arrived in 1682. It was first the property of Thomas Fitzwater who was on the ship with Penn when he sailed to America. The limestone deposits and subsequent kilns that were so common in the area led to the naming of “Limekiln Pike”, the first road leading out from the underdeveloped area and into Philadelphia. Limestone that was quarried and processed in the area was shipped to the port of Philadelphia and some was used to build Independence Hall. This house, expanded from its original size., was present when the British and American armies clashed at Edgehill and was certainly a landmark that soldiers passed during the American retreat to Camp Hill. Although previously under threat of demolition, today, the property has been preserved and is owned by the Lulu Country Club.

The Thomas Fitzwater House, located on Limekiln Pike in Upper Dublin, was one of the first houses built in Pennsylvania after William Penn arrived in 1682. It was first the property of Thomas Fitzwater who was on the ship with Penn when he sailed to America. The limestone deposits and subsequent kilns that were so common in the area led to the naming of “Limekiln Pike”, the first road leading out from the underdeveloped area and into Philadelphia. Limestone that was quarried and processed in the area was shipped to the port of Philadelphia and some was used to build Independence Hall. This house, expanded from its original size., was present when the British and American armies clashed at Edgehill and was certainly a landmark that soldiers passed during the American retreat to Camp Hill. Although previously under threat of demolition, today, the property has been preserved and is owned by the Lulu Country Club.

Twickenham

The remnants of an estate called Twickenham are located just north of Church Road where Grey and his soldiers once fought the Continentals during the Battle at Edge Hill. In early colonial days Twickenham was a stone farmhouse that served as the summer home for Thomas Wharton, Jr., a Philadelphia merchant and known supporter of the revolution. Wharton was first president of the Pennsylvania Executive Council. The name given to the place by locals was “The Governor’s Mansion” and Wharton was known for entertaining guests at the house. When the British soldiers struck Edge Hill on December 7, 1777, Grey’s troops fought against the Continentals all throughout the Wharton property. Thomas Wharton died only a year later in 1778. When the property was purchased by Robert Scott years later, the house and land underwent many transformations and updates. Today, only later wings that were added remain of the mansion. The original building was torn down in the 1950s. Today there isn’t much left of the original building that stood in December of 1777, but its location is still obvious.

The remnants of an estate called Twickenham are located just north of Church Road where Grey and his soldiers once fought the Continentals during the Battle at Edge Hill. In early colonial days Twickenham was a stone farmhouse that served as the summer home for Thomas Wharton, Jr., a Philadelphia merchant and known supporter of the revolution. Wharton was first president of the Pennsylvania Executive Council. The name given to the place by locals was “The Governor’s Mansion” and Wharton was known for entertaining guests at the house. When the British soldiers struck Edge Hill on December 7, 1777, Grey’s troops fought against the Continentals all throughout the Wharton property. Thomas Wharton died only a year later in 1778. When the property was purchased by Robert Scott years later, the house and land underwent many transformations and updates. Today, only later wings that were added remain of the mansion. The original building was torn down in the 1950s. Today there isn’t much left of the original building that stood in December of 1777, but its location is still obvious.

(N.B., please find sources and footnotes in digitized copy on Home Page.)